Jesus in Japan

Shingo Mura in Aomori Prefecture is by all appearances your average Japanese village in the idyllic countryside. However, Shingo is home to the キリストの墓 (Grave of Christ), based on a local legend about the visitation and death of Jesus Christ in the village.

During my inaugural ethnographic project from May 2008 to June 2008, I learned how the stuff of legend becomes a fixture of local culture.

To comply with my human subjects research approval, I have omitted confidential information.

The grave of Jesus Christ and his brother Isukiri in Shingo Mura

The Legend

According to the legend, Jesus Christ originally travelled to Japan at the age of 21 to study theology. He ended up living in the country for 12 years, during which time he learned the Japanese language and culture.

At the age of 33, he returned to Judea. However, when he was arrested and condemned to crucifixion, he escaped by swapping places with his brother, Isukiri.

He fled through Siberia and Alaska before finally arriving by boat at Hachinohe near Shingo Mura. Here, he lived the rest of his life in exile with a new identity (Daitenku Taro Jurai) and family. And here, he is buried on a hilltop marked by a timber cross.

My Role

As the sole researcher on this project, I designed the research plan, coordinated the logistics for arriving and working in the field, recruited research subjects, executed qualitative research methods, and analyzed the data for insights.

Road sign for the Grave of Christ in Shingo Mura

The Challenge

Previous journalist accounts of the legend focused on exocitizing or debunking the validity of the legend. Based on the “thick description” approach championed by anthropologist Clifford Geertz, I sought instead to study how the villagers understand and engage with the legend as a meaningful expression of their local culture.

My research was guided by the following questions:

- Who believes in the legend? Who does not? What do they think, feel, and value about the legend?

- What are the symbols, artifacts, traditions, and institutions connected with the legend?

- How does the legend fit into the lives of individuals, their community, and culture at large?

The Approach

Reading Up and Widely

Before arriving in Shingo, I learned as much as possible about the village and the legend from what I could find online and in the academic literature in English and Japanese. Given the obscurity of my research subject, my sources spanned an eclectic range: the Shingo Village’s website, tourist blogs, journalist accounts, and a few pages devoted to the folk legend in Mark Mullen’s Christianity Made in Japan. In particular, I learned about the history and nature of the legend, and the calendar of events and institutions dedicated to its contemporary experience.

Cultivating Empathy

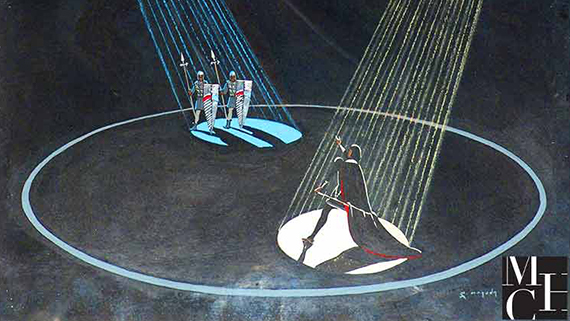

After arriving in Shingo, to empathize with the perspectives of the villagers, I conducted interviews with residents from a range of backgrounds (including age, gender, occupation, and interest in the legend), and observed and participated in the annual Christ Festival.

Mapping the Legend in Community Life

To understand the symbols, artifacts, traditions, and institutions connected with the legend, and their connection in turn with life in the village, I conducted contextual inquiries. I visited and studied sites connected with the legend, including the Grave of Christ and the Legend of Christ Museum; sites connected with the local tourist industry, including Maginotai Green Farm (a recreational facility); and sites connected with other local legends, like the Oishigami Pyramids.

Documenting the Local Legend in Japan

To explore other perspectives on the local legend within Japan, I accessed and conducted a document analysis of the local government’s archive of past Japanese publications and media footage about the local legend.

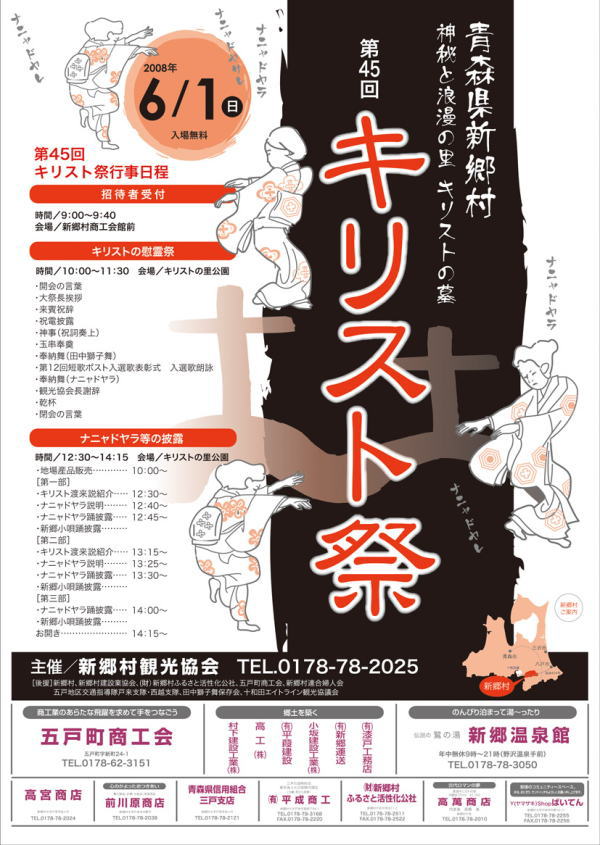

Artifacts of the legend: Grave of Christ jam, poster for the Christ Festival, billboard for tourist attractions in Shingo Mura

Insights

Through this ethnographic study, I learned about the process through which the stuff of legend becomes a fixture of local culture, creating new traditions, a sense of community, opportunities for tourism, and an entertaining sense of mystique.

Affection Over Faith

No one claimed that Jesus actually visited the village and was buried in the graves on the mountain—though one interviewee shrugged and qualified her statement, saying she was also not alive back then. Most understood and appraised the legend with the same affection as one would the Loch Ness Monster. Faith—in both the religious and secular senses—played a minor role, if any, and proved a relatively unproductive lens on the phenomenon.

A Fixture in Community Life

However, the legend clearly pulsed through the village’s community life. The village held an annual Christ Festival that drew the awareness if not participation of the whole community in its organization and execution. Local businesses produced and sold goods (sake, ramen, sweets, cups) based on the legend, and employed villagers to manage and care for tourist destinations like the Legend of Christ Museum. The local legend served to bring the community together in celebration, and occasionally into the spotlight of the media—locally, nationally, and indeed internationally as my very presence confirmed.

Legendary Meaning for Residents

At the end of the day though, the legend provided meaning for residents, a point hammered home to me when an elderly man showed me his personal library filled with books and notes about the legend, and a pair of tools for imprinting manju with an insignia of the Star of David (he was not Jewish), just in case one wanted to internalize the legend even more.

Manju tools with the Star of David

Sponsors

I am grateful to the Department of Anthropology, the University Research Council, and Associated Students of the University of Hawai’i (ASUH), all at the University of Hawai’i, for funding this project.

Related Projects

GradeSaver | UX Research and DesignEnhancing the GradeSaver website with user research, usability testing, and design

Mahindra Humanities Center | UX ResearchLearning about and supporting the needs and goals of the Center’s audience and community

Seminar Posters | Visual DesignDesigning posters to promote the seminars of the Mahindra Humanities Center

Genetically Modified Crops in Japan | AnthropologyStudying Japanese consumer perceptions of and activist engagements with genetically modified (GM) crops in Japan

Jesus in Japan | AnthropologyLearning how the stuff of legend becomes a fixture of local culture