Genetically Modified Crops in Japan

This longitudinal ethnographic research project was originally conducted between September 2008 and July 2009 in Tokyo and Chiba for my undergraduate honors thesis, with follow-up studies conducted between June 2011 and August 2011 in Kyoto and between June 2012 and August 2012 in Osaka for my master’s degree.

During this project, I studied Japanese consumer perceptions of and activist engagements with genetically modified (GM) crops in Japan.

To comply with my human subjects research approval, I have omitted confidential information.

Background

Since 1996 when genetically modified food and feed were first imported into Japan from the United States, Japanese consumers have grown increasingly wary of the place of such food in their diets. Consumer surveys conducted in 1997, 1998, and 1999 show that “70 to 80 percent of Japanese consumers typically express an unwillingness to eat GM foods.”

By 1999, this negative sentiment had become so ubiquitous that the Japanese government, in response to pressure by consumer and activist organizations, passed legislation to regulate GM food and implement mandatory labeling (effective as of 2001). Japanese consumer resistance and rejection of GM food has had resounding economic consequences for national food corporations, overseas producers, and farmers worldwide.

My Role

As the sole researcher on this project, I designed the original (2008-2009) and follow-up (2011, 2012) research plans, coordinated the logistics for arriving and working in the field, recruited research subjects, executed qualitative research methods, and analyzed the data for insights.

The Challenge

At the time of the study, published marketing studies and social science research surveyed and focused on what Japanese consumers think about GM food (e.g., in terms of general appeal and risk), but few paid attention to why and how they think this way. As such, the major aim of my project was to understand not only the attitudes and beliefs people have toward GM food, but also the situations, lifestyles, and culture that shaped their perspectives.

My research was guided by the following questions:

- What do Japanese consumers and activists think about GM food? When and where do they encounter and engage with GM food? Why and how do they formulate their attitudes and beliefs toward GM food?

- What are the major institutions and policies that define and regulate the circulation of GM food in Japan?

- How is GM food represented in different spheres of culture?

- What are the values, traditions, and norms of Japanese food culture in general? How does GM food fit (or not fit) in with this culture?

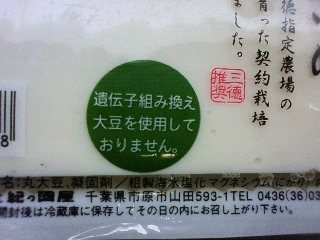

Food labels that declare the ingredients of the product are “Non-GMO”

The Approach

Familiarization with the Science and Public Outreach Issues of Genetic Modification

Beyond academic coursework in the Japanese culture and language, I studied molecular biology and worked for the Biotechnology Outreach Program at the University of Hawai'i from 2006 to 2008 (and upon my return from the original project, from 2009 to 2010). As part of the program, I facilitated public education and outreach efforts about genetically modified crops in Hawai’i for the general public and elementary school students, and conducted a literature review on worldwide perspectives on genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

This background in both the science and public outreach issues of biotechnology provided a foundation for discussing often technical and controversial subjects with activists, scientists, government officials, and industry representatives.

Reading Up and Widely on Japanese Food Culture

To understand the values, traditions, and norms of Japanese food culture in general, I conducted a literature review of the anthropology of food in Japan. I also analyzed Japanese cook books, foodie books, food company websites, and food packaging labels.

Delineating Consumer and Activist Perspectives on GM Food

To familiarize myself with Japanese perspectives critical of GM food, I first conducted interviews with local activists from Greenpeace Japan and the NO! GMO Campaign. However, I realized through our conversations that consumer cooperatives powered by housewives played a larger role in shaping the public antipathy toward GM food, both through their prominent voices in public policy debates and their responsibilities for food in everyday domestic life.

As such, I extensively interviewed housewives and members of the Seikatsu Club consumer cooperative, as well as college students (who were grew up at home in the same era when GM food began to be imported into Japan).

I also distributed a survey through the Seikatsu Club consumer cooperative.

Understanding Engagement with GM Food in Everyday and Political Contexts

As a way to understand the settings in which consumers encounter and engage with GM food in everyday life, I conducted contextual inquiries at local supermarkets and the store and restaurant of the Seikatsu Club consumer cooperative.

To understand how consumers and activists engage with GM food in explicitly political settings, where they can voice their opposition to institutions like the government and media as well as share their experiences with one another, I observed and participated in a government-sponsored public forum on the safety of GM food. After the public forum, I moderated a focus group with participants about their experience at the forum.

I also observed and participated in a “GM canola inspection” with activists and the Seikatsu Club consumer cooperative, which sought to identify and record the location of GM canola illegally growing in the wild.

The site of the “GM canola inspection”

Mapping the Role of Institutions and Policies

To understand the major institutions and policies that define and regulate the circulation of GM food in Japan, I performed interviews with scientists researching GM crops (in the public and private sectors), domestic and foreign government officials (i.e., the Society for Techno-Innovation of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries [STAFF] and the United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] Foreign Agricultural Service [FAS]), and agribusiness representatives (e.g., Monsanto Japan).

I also analyzed policy and scientific documents, including government white papers, the Food Sanitation Law related to the labelling of GM food, and safety assessment reports by the government’s Food Safety Commission on GM maize and soy.

Discovering Diverse Cultural Representations of GM Food

To understand how GM food is represented in different spheres of culture—ranging from politics to popular culture—I collected and analyzed a range of texts that discussed or referenced GM food, including:

- Newspaper articles focused on risk and food safety

- Activist publications criticizing public policy and safety assessments

- Political campaign posters highlighting GM food as foreign food

- Graphic novels (manga) featuring GM food in dystopic science fiction

- Children’s books moralizing on the dangers of GM food for Japan and purity of domestic agriculture

- Government brochures discussing the science, history, and safety of GM food

- TV commercials featuring “bean-dog” (mameshiba) genetic hybrids as mascots

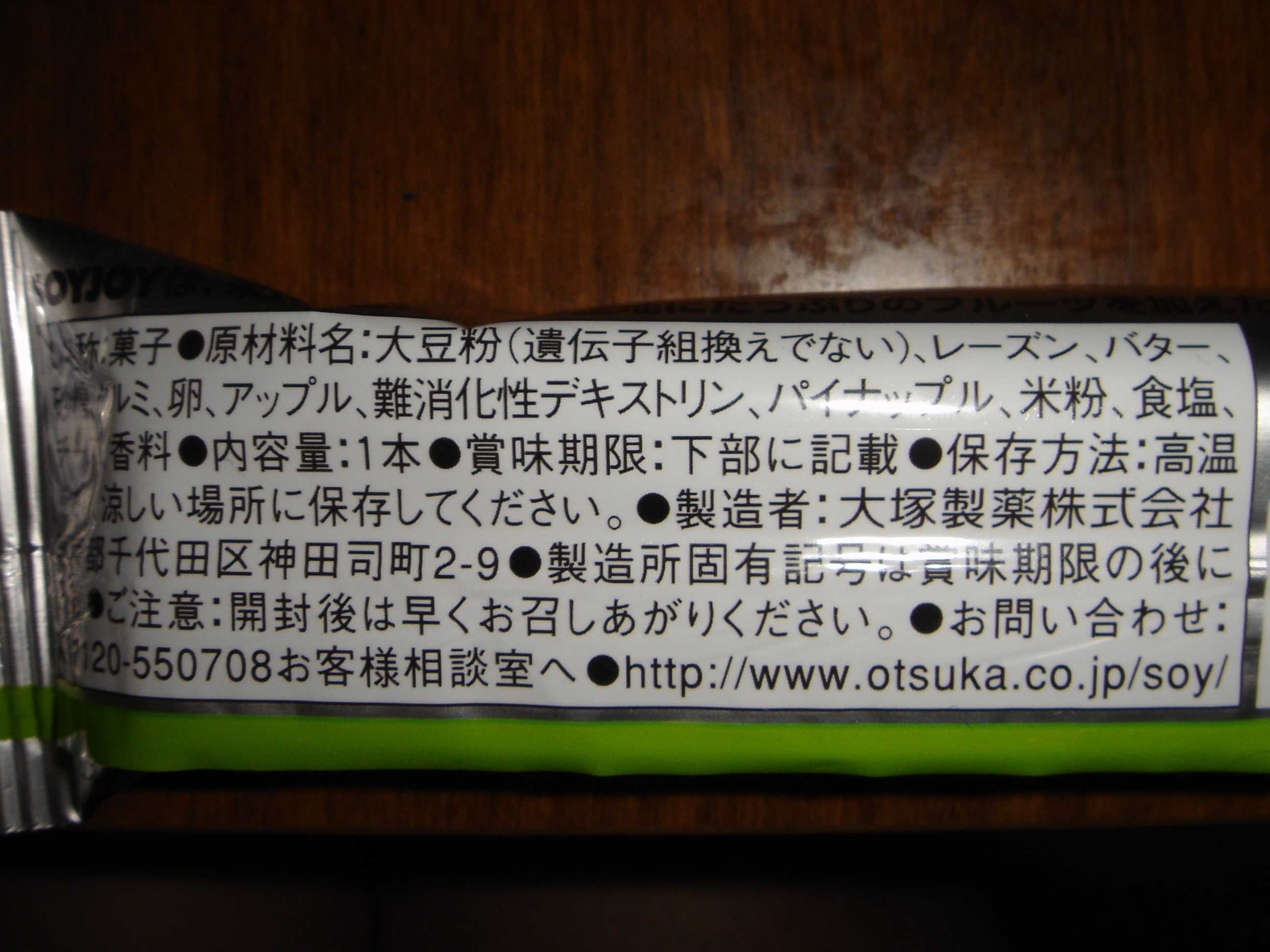

Featured photo of questionable (GM) soy from the True Food Guide by Greenpeace Japan

The Discovery

The Two Dimensions of Safety

Popular in descriptions and advertisements of food in Japan is the paired phrasing, anzen (physical safety) and anshin (the feeling of safety). Yet, all too often, governmental, industrial, and scientific discourse and texts about GM food center around anzen, measured in terms of objective risk and downplayed as a matter of control and regulation. Fears and uncertainties about the unknown consequences of GM food, particularly for the health of future generations and the environment, become marginalized as unreasonable and emotional anshin, symbolized by images of anxious housewives and paranoid activists.

GM Food Lacks Desirability

However, without a sense of anshin, consumers will remain wary of GM food, which was oftentimes discussed in the same breath as then contemporary food scandals like imported rice with poisonous mold, imported dumplings contaminated with pesticide residue, and imported milk with toxic industrial chemicals. Like these imported products, GM food comes from a faceless foreign source and carries a sense of being tainted. In this way, GM food does not fit into the Japanese cultural framework for desirable food that emphasizes domestic production, local connection, and purity in content and form.

Food Labels Create Anshin Through Avoidance

The government’s response to consumer and activist discontent toward GM food in the 90’s—food labels to distinguish GM from non-GM food—mitigated the situation to an extent. Food labels addressed consumer demands for choice and theoretically allowed them to avoid ever eating GM food. Labels with “idenshikumikae denai” (not genetically modified) were ubiquitous in supermarkets I visited, and most of my interviewees were confident they never bought or ate GM food (except maybe at fast food restaurants with unlabelled products). Of course, food labels also reified the idea that GM food must be monitored and segregated, thus creating anshin through avoidance.

GM Food as a Regulated but Actively Contested Absence

That being said, I never encountered a single food product labelled as a GMO in Japan, despite the fact that Japan is the largest per capita importer of GM food and feed in the world. Granted, the Japanese food industry has typically paid a premium for segregated, non-GM crops like corn used for human consumption to avoid consumer backlash. Yet, as several activists pointed out, the labelling law requires food manufacturers to apply a label declaring its product as a GMO only if over 5 percent of the total weight of the food item consists of a GM ingredient; furthermore, oil derived from approved GM soy, canola, cottonseed, and corn are exempt. This enables, for example, an estimated 10 percent of soy sauce manufacturers to use GM soy meal without specifically labeling their product as such.

For this reason, many activists and concerned consumers continued to focus on consciousness-raising events, like the Seikatsu Club’s GM canola inspection, to highlight the presence of GM food and feed—or in their words, “idenshi osen” (genetic contamination)—in Japan.

The Impact

The results of this study have been published as journal articles in Lambda Alpha Journal and Appetite, and were presented in 2 invited lectures at Waseda University (Japan) and Monash University (Australia) as well as in presentations at 6 national conferences by the American Anthropological Association; Japanese Studies Association; Association for the Study of Food and Society; Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society; and Society for the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition.

For my research, I was awarded the 2010 (National) William White Prize by the Association for the Study of Food and Society.

Sponsors

I am grateful to the US–Japan Bridging Foundation, University of Hawai’i Foundation, University of Hawai’i Colleges of Arts and Sciences Alumni Association (CASAA), and University of Hawai’i Arts and Sciences Advisory Council for funding this project between 2008 and 2009.

I am also indebted to the Reischauer Institute at Harvard University for funding this project between 2011 and 2012, and to the Japanese Studies Centre at Monash University for hosting me as a Visiting Scholar in 2012.

Related Projects

GradeSaver | UX Research and DesignEnhancing the GradeSaver website with user research, usability testing, and design

Mahindra Humanities Center | UX ResearchLearning about and supporting the needs and goals of the Center’s audience and community

Seminar Posters | Visual DesignDesigning posters to promote the seminars of the Mahindra Humanities Center

Genetically Modified Crops in Japan | AnthropologyStudying Japanese consumer perceptions of and activist engagements with genetically modified (GM) crops in Japan

Jesus in Japan | AnthropologyLearning how the stuff of legend becomes a fixture of local culture